By: Richard Van Heertum

The problem

Reverbs, remakes, repetition, trite recapitulation, simulacra, spectacles, echo chambers of sameness, unsavory succubae, blood sucking vampires of originality.

All these terms and phrases seem to capture an obsession that has beset the Hollywood of today, though some a smidgen more harshly than others. The industry just seems to have given up on original storytelling, at least when big money is on the line, preferring to continue feeding at the same trough for as long as the river of dollars flows through. And audiences, forgoing occasional protestations or discontent, seem content to ride that same hackneyed river, attending these festering blisters of banality in big numbers no matter what the critics, or commonsense, might otherwise suggest.

The depths of this obsession are clear for anyone to see, most recently exemplified by the film that got Jack Nicholson out of a seven-year unannounced retirement – a remake of German hit Toni Erdmann, a tenderly funny character study released just last year. Or maybe we should just point to Fifty Shades Darker, a follow-up to the largely unwatchable but billion-dollar-grossing PG-13 take on S&M, a remake so bad that even the sex was boring. The most obvious offender is the endlessly rehashed world of Superheroes, but we shouldn’t ignore the stream of sequels from Star Wars and Star Trek, of never ending horror franchise entries, of Adam Sandler’s tired exercises in masculine inanity or the reboot of one old ’80s movie or TV series after another.

The question

The obvious question as we embark on our adventure into deconstructing the reasons for this neurotic recapitulation is: where did it all begin?

It hasn’t always been like this, right? How did things used to work? How did Hollywood make money before the Dark Times, before the Endless Sequel.

Back in the day, before sequels of sequels

The Hollywoodland sign, old style.

Our story commences as the center of the film industry moved from France to New York and then onto an area of that sleepy old city-cum-suburban patchwork Los Angeles known as Hollywoodland. Back then, it was a Wild West of creativity, a group of groundbreaking filmmakers plying their foray into this new art form alongside a series of mostly immigrant, mostly Jewish capitalists that were adventurers themselves. The movie industry itself got its humble start from the Kinetoscope shorts of Thomas Edison and the actualities of two French camera manufacturers, who saw no future in their invention. However, within two years of the Lumière Brothers first showing their short films to a paying audience in the basement of the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris in 1895, it had been seen by audiences across the globe. Edison, in particular, was mesmerized by this new art form and its potential to bring in giant boatloads full of cash.

But though Edison and Edward Porter would move the industry from its short, documentary beginnings into the world of narrative film, there was a host of others who would play a leading role. Charlie Chaplin, though remembered now as the master of silent comedy, was among the first to fully realize the artistic potential of film, moving from studio to studio before starting his own, United Artists, with the dashing Douglas Fairbanks, the entrepreneurial Mary Pickford and one of the masters of the silent era, D. W. Griffith. Griffith would build on the work of other early filmmakers to create the visual language still used in films to this day. The Soviet Montage directors, who took their lead from Griffith, and German Expressionists expanded on the tools at the disposal of Hollywood and together forged the way forward for film when its first sea change arrived.

Let’s jump forward a bit, to the moment when sound first appeared alongside pictures: 1927’s racially-troubling hit The Jazz Singer. The old stars of the silent era quickly disappeared, along with 70% of their pictures, as the new technology offered spectacle on a heretofore unrealized level. The musical was born, with Busby Berkeley taking inspiration from the most unlikely of sources, the army, in building spectacles that wowed audiences until Fred Astaire came along to replace lines of dancers with a single pair in motion. He was joined by Cecil B. De Mille, who had to stamp down his ambitions after the studios discontent with his widely over budget Ten Commandments and instead turn to the chambermaid view of the wealthy that captured the imagination of a country in the throes of the Great Depression. And then there was the premier director of the 30s, Frank Capra, who won three Oscars with a slightly less saccharine version of the American Dream than his later films like It’s a Wonderful Life – now beloved, but panned for its maudlin sensibility by critics of the time.

Hollywood’s formulaic Golden Age

Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland in The Adventures of Robin Hood

The formula that Hollywood was developing in the ’20s and ’30s would lead it through its “Golden Age” (~1928 to 1962) with great aplomb and greater profits. That formula was simple but brilliant, building on the profit-making strategies of the silent era.

The first component was the business model, of vertical integration, where the “big five” studios – Paramount, Warner Brothers, RKO, MGM and 20th Century Fox – had oligopoly power over both the production and distribution of their films, owning 70% of the theaters in big cities and 60% of those in smaller cities. This was backed by block booking, where the studios would sell the entire year’s slate of films before even completing them, with the theaters having little choice but to comply and provide the studios with guaranteed profits. They were supported by the “little three” studios – Universal, Columbia and United Artists – along with a host of other small studios and independents, who would fill in the gaps with genre and sub-genre films and the occasional hit of their own. And they ensured that cost overruns were limited by following strict production timelines.

The second component of the Hollywood formula was that the studios controlled not just the production and distribution of their films, but also controlled the talent. They locked up writers, directors and actors with long term contracts and perpetrated the Star System, a model of cinema consumption, marketing, and production that was built around beloved personalities and typecast roles. The Star System functioned as a star-making empire, where they would teach their top actors and actresses to talk, dance, sing and comport themselves in ways appropriate to their public persona (this is the entire (super meta) plot of Singin’ in the Rain). They quickly realized that audiences fell in love with these stars, particularly after the realization that the close-up was an instrument of projection that could animate the hopes, dreams and desires of those audiences. To keep the stars in the news, they developed a whole coterie of supporters including gossip columnists, celebrity rags, mainstream news coverage and awards ceremonies (the Academy Awards were launched in 1929), alongside very public love affairs, marriages and beards for the homosexuals among the stars.

Beyond these business strategies, though, was the real genius of their empire-building plan – the psychology of film. Hollywood, unlike Europe, recognized that film was a powerful psychological mechanism to entrance audiences looking for stories that had the happy endings so hard to find in real life. The narrative formula was founded on closed romantic realism, where characters with clear goals faced a series of obstacles on the road to ultimate triumph, in love, war and life itself. Hollywood didn’t trust audiences to ferret out the nuances of character or story, instead relying on one of its other great innovations – the reaction shot – which effectively told audiences what to think before they ever had time to consider their own response to a scenario.

The next component of the Hollywood formula was a holdover from an earlier era, the realization that audiences wanted predictability in the films they watched. They wanted to know in their Romances that the girl and boy would end up together, in Westerns that good white guys in white hats would win out over evil black hats, in Musicals that the movement of bodies was ultimately a movement toward love, in Gangster films that, after allowing them to live a vicarious thrill, the bad guys would get their comeuppance in the end, and so on. And so, genre consistency became a rule only broken on occasion, essentially following the formula of giving audiences what they wanted. These genres have largely persisted from the earliest days forward to the present, with a few added along the way, including sci-fi in the ’50s and a whole host of sub-genres and mixed-genre films like teen comedies, comedic horror and the like since the ’80s.

The final element of the formula was for the studios to self-censor themselves, afraid as they were, that audiences might question the themes they were purveying to audiences young and old. When parents started to question the excessive violence and salaciousness of films in the ’20s, they quickly adopted the Hays Code, which severely restricted the sexual, violent, racial and anti-nationalist messages of film. When Joseph McCarthy and HUAC emerged as a political force in the late ’40s and ’50s, the industry first scapegoated the Hollywood Ten and then established a decade-long blacklist that barred actors, writers, directors and producers from formal participation in the industry. More recently, we have seen this continued tendency with several blockbusters like Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol and Zero Dark Thirty, altered to get past the Chinese Ministry of Culture and the CIA.

The postwar crackdown

Film director Edward Dmytryk, a member of the Hollywood Ten, answers questions before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, April 25, 1951

So, even as the country plummeted into a Great Depression that lasted, in varying forms of hardship, from 1929 to the end of World War II, Hollywood continued to prosper. However, as profits began to sag in the 1950s, the studio gave up on social problem films (about one in three films made between 1946 and 1952) that had challenged the earlier model of trying to offend no man or women, they doubled-down on the formula that had served them for the better part of two decades. Genres came back into vogue, with only the new addition of the sci-fi thriller to the fold. They developed the modern blockbuster, with Cecil B. DeMille the great purveyor of this new form – spectacle-oriented historical epics like The Ten Commandments, and The Greatest Show on Earth, though we can also look to the work of Preminger, Wyler, Ray and the great underappreciated David Lean (The Bridge on the River Kwai, Doctor Zhivago, and Lawrence of Arabia, to name three of his masterpieces), among a host of others. Hollywood also whitewashed out most overt political themes, blacklisting the socialists who had written so many of the great films during and after the war and returned to the comfortable middle-class values and closed romantic realism that has dominated the industry through most of its history. Formulaic genres again dominated, with John Ford pumping out one Western hit after another, Hawks, Huston, Wilder and Curtiz carving out Film Noir hits, Stanley Donen modernizing the Musical, and a host of others plying their craft in the worlds of Horror, Comedy (which did suffer in the ’50s, hamstrung by taboo subject areas), Gangster films, and Romance.

The Paramount Decision of 1948 ended the vertical integration of the past, with the studios forced to sell their theaters, but they turned to new technologies to challenge the growing competition of television, with stereoscopic sound, wide screens, the expansion of drive-in theaters and Technicolor combining with gimmicky advances like 3D, Smellorama, Hypnovista and Duo-Vision. The spectacle, which had existed on the margins of the industry from De Mille’s early silent blockbusters to Griffith’s bigger productions, was now in vogue and would only expand, with only a short break for the American New Wave, to dominate the industry to the point where today the big studios plan their year around four to six big budget, tentpole hits, with everything else secondary.

Let 100 auteurs bloom: The experimental American New Wave

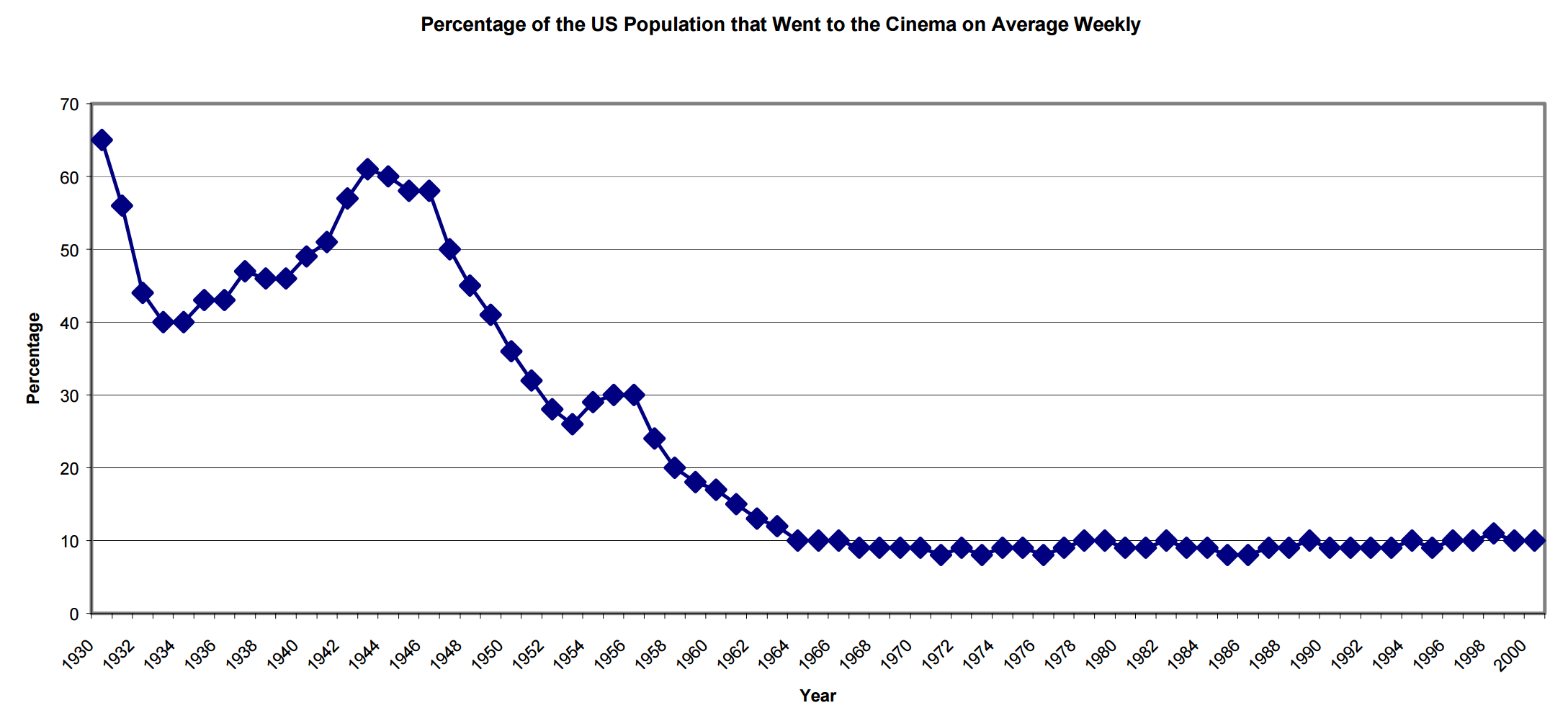

Graph and data from Michelle Pautz, “The Decline in Average Weekly Cinema Attendance: 1930-2000,” 2002.

That strategy worked for a time, but, after rebounding, ticket sales began to plummet anew throughout the ’60s, falling from a high of 130 million tickets sold a week in the late ’20s and after WWII down to 19 million near decade’s end. Unsure how to move forward, the industry made its biggest gamble yet, putting their financial futures in the hands of young, countercultural American auteurs, inspired by the more intellectual and personal stories of their European and Asian forebears from Truffaut, Godard and Kurosawa to Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman and Resnais (to name but a few). Starting in 1967 (one of the signature years in the history of Hollywood alongside 1939), a host of films exemplified the changing face of tinsel town. The most iconic was Bonnie & Clyde, directed by the television-to-film convert Arthur Penn. New techniques in cinematography and editing converged with more frank treatment of sexuality and more graphic violence, turning the heads of directors, editors and actors alike, after getting a sizable push from the iconic critic Pauline Kael. The same year saw the youngest director to ever win an Academy Award, Mike Nichols, do so with his second feature, the masterfully funny The Graduate.

A new movement was born, led by American auteurs more interested in experimentation, rawness, realism, graphic violence and sexuality and revitalization over formula. Among the most famous are John Cassavettes, who launched gorilla filmmaking with his surprising hits Shadows (1959) and then Faces (1968), Robert Altman, Scorsese, Coppola, Ashby, Bogdanovich, De Palma, Mazursky, Pollack, Friedkin, Lumet, Pollack, Schrader and Dennis Hopper, though the full list is much longer. The group were driven to make films as art for the increasingly young, college-educated audiences who had been weaned on the independent hits of European and Asian cinema. Each of the tenets that once made Hollywood successful were challenged and then abandoned, with producers, directors and stars creating their own teams, dealing more explicitly with taboo topics, turning away from the middle-class values and happy endings that were manna to the industry and redefining or abandoning the genres that audiences had come to embrace. Briefly.

Ironic, then, that this experimental decade would also see the birth of the blockbuster, beginning the great shift in Hollywood back towards a focus on safe, predictable, unoriginal profits.

Next up

We look at the birth of the blockbuster, and how a movie made for the eight-year-old sci-fi buff launched a thousand copycat franchises.

No Comments on "The Endless Story: Hollywood has always loved a good formula"