By: Patrick W. Zimmerman

The Question

Can a hypothetical Gamer Girl play as a character that is, ::gasp!::, also one of those sneaky womenfolk?

Often! Increasingly often!

As games have grown in popularity, they’ve lost much of the strong association with a teenage male social outcast archetype developed through the 1970s and 1980s. Electronic gaming has not been an outcast’s pastime for decades, and it was almost certainly never as male dominated as the Mainstream Media™ would have had you believe (much like its predecessor as the emblematic nerd pastime – tabletop gaming). Studies of the actual number of gamers worldwide are scattered and sketchy, but all conclude that the number is massive, particularly when one considers the massive adoption of mobile games. According to the Entertainment Software Rating Board (The ESRB),1 members of roughly 2/3 of US households played games by 2010. The Entertainment Software Association (a major industry group) estimates the number at 150 million-plus Americans as of 2015. The estimates worldwide posted on online statistics aggregator Statista claim 1.78 billion nerdz exist in the world, though definitions are conveniently hidden behind a premium paywall. Even hedging massively given the paucity of data available from non-industry sources (translation: self-interested promoters), it is clear that the nerds have arrived. Any time that a claim can be made that a quarter of the world’s population has participated in some common activity in the last year without it seeming orders of magnitude out of whack, we are no longer talking about a niche.

Great. More people are playing games. Happy fun party times! What could be problematic about that?

Misogyny. Sexism, like many other forms of prejudice, can be rampant in the dark underbelly of the internet, the shield of anonymity providing a platform for the worst elements of our collected social tensions to express themselves.

Apparently, a prominent, vocal, and passionate minority find the subculture’s move from fringe to mainstream not a triumph of the art form but a diluting of its authenticity (and exclusivity). And they have often expressed this discomfort through vicious and persistent harassment of prominent women developers, gamers, and cultural commentators, most infamously under the disparate series of harrassment campaigns collectively called “GamerGate.” Basically, a segment of OG gamers have coalesced into the real-life embodiment of the Get Rid Of Slimy Girls Club.

It’s a losing battle. The ESA’s 2016 Essential Facts survey of 4,000 US households concluded that 41% of gamers are now female, with adult women (over 18) almost doubling the percentage of pimply boys (under 18), 31% to 17% of the market.2

A month ago, I ran a pilot study of the highest-rated games over the last 20 years. Using the aggregate review archives at Metacritic.com,3 I wondered if recent critically-acclaimed games with women protagonists were part of a wider trend. Were Her Story and Life is Strange flashes in the pan, or were game studios starting to realize that, these days, everybody plays games. Women, too.

The pilot suggested that, you know, there might be something to this resurgence idea, and that yes-of-course-20-games-is-a-ludicrous-sample-size, so I took the time to go through and run the study on the Metacritic Top 100.4

The short version

The pilot results held up, with the sex breakdown of the Top 100 eerily matching the curve of the Top 20, even if you break out the latter to avoid overlapping datasets (comparing #1s 1-20 to 21-100).

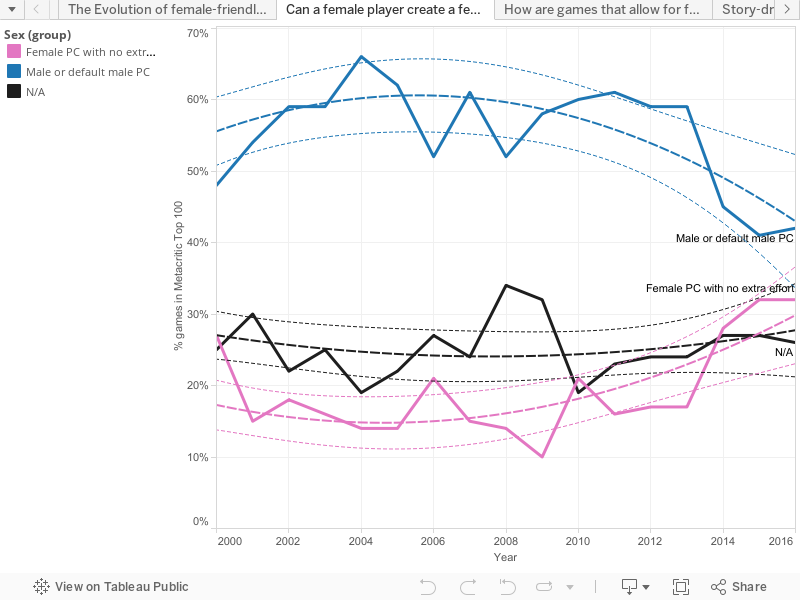

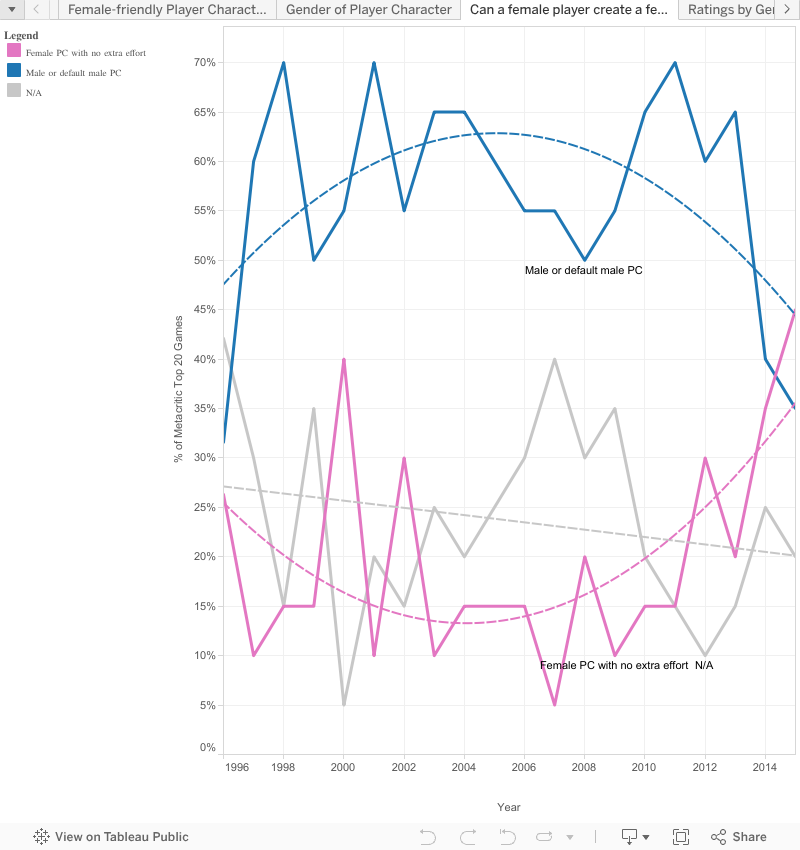

In the last 2 years, there’s been a major shift in gaming with an increasing percentage of female player characters. In looking at the most high-profile games, female-friendly games used to be moderately prominent (before 2001). Then they weren’t at all (2001-2013). Then, suddenly, in the last 2 years, there’s been a major resurgence of games that enabled a player to play as a female PC with no extra effort (meaning either a default female PC or a customizable one). From 2001-2013, the percentage of male or default male player characters was never lower than 52% of the Metacritic Top 100. Starting in 2013, it dropped from 59% to 45% to 41%. In the same time period, the female and custom percentage of the Metacritic Top 100 never topped 21%….until the last two years (27% and 32%, respectively).

Translation: yes, the industry is trying to woo more ladies. Collectively, gaming studios are betting on games that have more women characters. The likely implication is that this is based on a gamble more women will be attracted to games with more women in them. Rocket science.

Results that were exactly what I thought they would be

Q1: Can a female gamer create a female PC without undue effort?

The only surprise in moving from the pilot study that started this project to the more extensive Top 100 study is how little difference there was in the sex distribution of player characters. Bro Valley, Land of sports games and glorious small-arms squad tactics, is alive and well.

Click image for full dashboard

If you look at the two sample sets side by side, they look almost identical. Seriously, the Top 100 is basically just a smoothed version of the Top 20. Creepy. The correlation between the % of female-friendly PCs in the top 20 and the next 80 is a whopping 0.91.5

Click image for full dashboard

Results that made me go, “Huh. That was weird.”

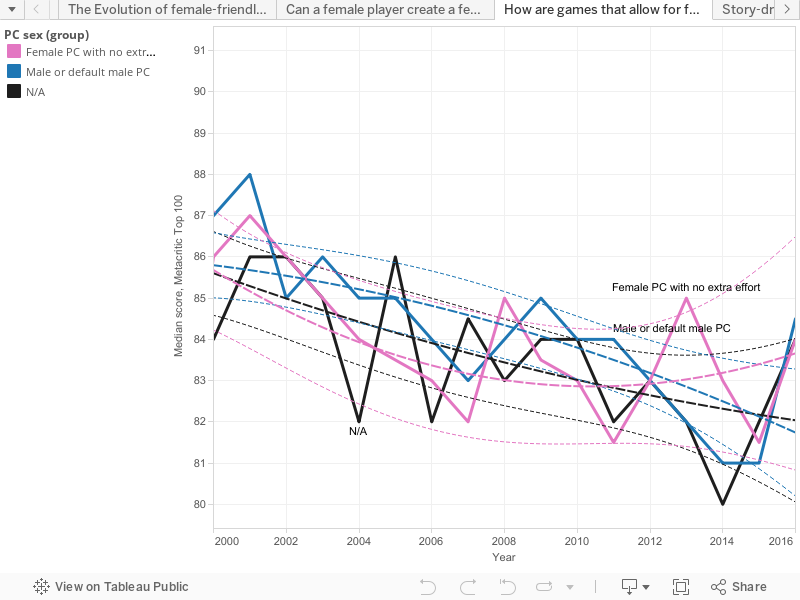

Q2: Is favorable critical reception for female-centered games driving this change?

Ehhhhhh. Not really. The ratings are kind of all over the place, and the only real strong result is that as gaming has matured as an entertainment medium, critics have gotten more skeptical. Grade inflation, though, is still totally a thing (the median metascore for a game in 2015 was 73 on a scale of 0-100, across 641 titles).

Click image for full dashboard

Q3: Are story-driven games becoming more common, and does that parallel the focus on female-friendly PCs?

Nnnnoooope. The story-driven data is all over the place and miiiight be trending up, but that’s about it. Unlike the pilot study, where the story and female-friendly curves matched each other suggestively, when I expanded the study, the similarities broke down.

What next?

To quote my favorite letter of the alphabet, “Y?”

It’s quite clear that there is significant change over time in how games have been designed. We’ve established a “what.” That’s nice. Not thrilling, but nice. It’s an axiom here at Principally Uncertain that the real interesting problems involve trying to figure out what is driving that change. We really want to look for “why?”

Thus, a few ideas for follow-on projects seem potentially fruitful:

- At some point, I plan on leaving Mr. Leonard (Science! Mascot) and quantitative methodology behind for a bit, with a follow-up series of interviews with female gamers of various ages, looking at how their experiences with gaming have evolved over time.

- A useful (and kinda hilarious) project would be to look at the 100 worst games of each year and compare the patterns to the Top 100.

- Another clear line of investigation is to compare PC sex to genre. Custom player characters, for example, have long been a staple of role-playing games going back to their pre-electronic origin in Dungeons & Dragons (1974). Sports (as noted above) has been the bro-iest of bro genres.

- How has the rise of franchise games (mirroring a similar pattern in movies) affected this? Are indie games more likely to vary protagonist type?

The bottom line

So, what does this all mean? Well, it’s clear that women are both playing games more often and that, recently, there’s been a significant move to try to cater to that audience by the PC and console gaming industry (mobile games have been targeted at both women and men for some time). Most significantly, this is an indicator that game producers have started to (finally) modify their conception of “serious” gamer. It is no longer (always) assumed that the ladies are wasting their time with frivolous Facebook games like Farmville or Words with Friends. Their first choice in interactive entertainment might have a higher degree of narrative depth than Bejeweled or Tiny Tower. Conversely, it might even be true that a secret underground cabal of self-identified gamer doodz play (::shudder::) mobile games as well.6

It’s encouraging to see the sex ratio of gaming protagonists starting to reflect the makeup of games’ audience. Encouraging, in the short-term, at least. It remains to be seen whether or not this move continues over the long-term, as cultural shifts are rarely seen in a mere two-year timespan. Currently, 48% of women play games but only 6% identify as gamers.7 One plausible factor behind that disparity is that women simply have not felt like the gaming industry really thought of them in those terms. If, as in the early 2000s, game studios decide to re-start the frat party, the last two years will end up as little more than a curiosity. A momentary blip. This could happen because of a technological advance that allows studios to move product based on novelty alone,8 a crash or consolidation in the industry (see 1983), or some random misogynist deciding he wants to run for President of Gametopia after losing the 2016 election (not thinking of anyone in particular here. Nosiree).

I hope it isn’t just a fad. The ability to experience stories from the points of view of a wide variety of characters is one of the great untapped possibilities of games as interactive narratives. The performative nature of the genre means that a 17 year old boy in Illinois can, nearly literally, attempt (and enjoy) seeing things from the perspective of a 43 year old bisexual schoolteacher in Meiji Japan.9

In summation: this is a good start, but it needs to continue for several more years to have a significant effect on the way gamers consume games, the way they see themselves, and the way society views them. Will gaming become truly mainstream, rather than the kind of oddly underground mass cultural phenomenon nerdhood is currently?

Call me crazy; I’m cautiously optimistic.

Notes:

1 You know, the group that advises parents about whether Doomblastathon 3000: The Headasplodering is perfectly safe for their 17 year old to play but likely to cause severe violent tendencies in their 16.5 year old. ^

2 Methodological details of the survey were not included in the circulation, which is heavily infographic-itized, so take the exact numbers with a hefty helping of salt.^

3 This includes games made for consoles, PC, and handheld platforms (i.e., PSP, Gameboy Advance, Vita, DS, 3DS, etc.). iOS and Android versions of games are not included.^

4 Each game was only counted once, at the highest-scoring platform in the year of its first release (so no ports, remakes, DLCs, or special editions), then sorted by sex, genre, and whether or not it was story-driven (is the narrative a major reason people play the game?). I ended up truncating the time period from 1996-2015 (pilot) to 2000-2015 because very weird stuff happens at the bottom end of the ratings in those early years (when there were less than 100 games that hit Metacritic’s 7-review minimum).

The number of games reviewed rises rapidly at the turn of the century. From 19 in 1996 to 52 in 1999 to 343 in 2000 to 545 in 2001. In 2015, 867 games qualified. The list of gaming publications (print and online) that Metacritic aggregates can be found here. ^

5 Coefficient of Correlation, so -1 means a perfect negative relationship, +1 means a perfect relationship. Thus, R=0.91 is a near-perfect match. For those of you who love linear regressions instead, R2=0.82.^

6 Raises hand. Guilty.^

7 See: Maeve Duggan, “Gaming and Gamers,” The Pew Research Center (2015), .^

8 Sorry, Oculus Rift fans, VR probably won’t be that breakthrough in the same way that the vastly improved graphics engines of the PS2 / Gamecube / Xbox and 3D accelerated PC video cards fueled a wave of 3D graphic shooters and sports games.^

9 This would be a cool idea for a game. You can have it for free, as long as you actually turn it into a game. Devs of the world, make it so!^

No Comments on "Beyond Ms. Pac-Man: The return of female player characters"