By: Patrick W. Zimmerman

Calling all Outdoor Nerdz! Hey, amateur naturalists, bio majors who took too many field courses and not enough labs, and grown-up boy scouts (you know who you are), it’s time to engage in one of our passions here at Principally Uncertain: placing hyperbolic importance on relatively trivial things!

You know what’s been missing from your life? Trailmetrics.

Sure that 3-day through-hike you did last May in the Grand Canyon was pretty epic, but exactly how awesome was it? Can you compare yourself to the woman we met in Glacier this September who casually mentioned, among other things, that she had walked there from [frickin’] Mexico?1

Major thanks to Richard Sharp for discussing this with me for many many miles. And to Alex and Euge for not stabbing us to make it stop.

The Question

Can we create a holistic measurement for the two factors hikers care about most: Degree of Difficulty and Payoff? And then make a big database and map to share with the world?

Yes. Yes, we can.

The Rules

Well, not so much “rules” as “guidelines.”

- The journey has to be primarily on foot. There is one exception, the namesake for our degree of difficulty measure: John Wesley Powell. He gets a pass because he was a one-armed man in a wooden rowboat strapped to a goddamn chair rafting the Colorado.2

- Any assistance railing, ropes, or piton assistance must be part of the trail. No actual mountain climbing or rappelling in caves. The Half Dome cables count. Climbing up the face of Half Dome? That’s a total badass thing to do, but it’s not hiking a trail.

Degree of Difficulty – HARM

Both of these metrics are going to need to be scaled to a rate measure, because it’s a lot easier to compare trails of (typically) wildly varying length when taking the average difficulty of equal length units.

We’ll tackle degree of difficulty first because, ironically, this is the easier of the two metrics to pin down and the one with more reliable sources. We’ll meassure Hiking Above Replacement Mile (HARM) in Powells per mile, where 1000 Powells/mi = 50% expected mortality. One hopes none of our readers never approach that number. The measure pretty naturally breaks down into two main components: Difficulty and Risk.

I’ll slightly re-define Difficulty as “work”, and we can measure it as mass times distance. The mass of moving a pack is not quite the same thing as the total mass moving across the trail (since you are moving yourself), so we will use relative mass instead (the percentage more massive you are with your pack), which nicely accounts for the fact that I can carry a 30lb pack without straining myself too hard but @rsharp’s 4 year-old would be basically doubling his mass. Additionally, “10mi” and “10mi with 2000ft of cumulative elevation gain” are quite different things. It looks like there’s no definitive standard on how to do this, but a lot of rules of thumb. Here’s one thread discussing the issue, and here’s another blog post. One thing that looks pretty set is that most people take a baseline of +1mi equivalent for every 1000ft of elevation gain and then adjust for their own particular experience. Lacking any other convincing evidence, I think I’ll just go with that. Put it all together, and we get: ((Masshiker+pack / Masshiker) x ((cumulative elevation gain in ft / 1000) + distance)).3

Risk can be simplified to a mortality rate. The National Park Service’s Office of Risk Management appears to keep track of these but….they don’t make them particularly easy to find. If it proves too troublesome to get the raw stats out of Washington, we can try and use that great unwalled database, Wikipedia, to look for deaths of the more sensational kind (animal attacks, while a miniscule percentage of accidents in National Parks, tend to get enough press to get logged. So while we hope to be able to include risk of death by drowning, auto accident, and selfie,4 we may have to approximate to bad luck, bad karma, and plain idiocy that actually results in a coroner filing a report.

In short: HARM = (((Masshiker+pack / Masshiker) x ((cumulative elevation gain in ft/1000) + distance)) x (mortality rate x 2) x 1000 ) / distance

Why multiply by 1000? Because otherwise the numbers are so small as to be meaningless most of the time. Guess how many miles (roughly), John Wesley Powell’s expedition was?

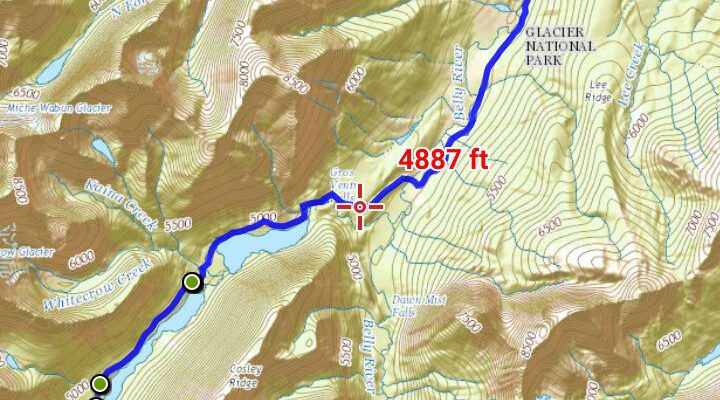

Let’s run the example of @rsharp and my hike up the Belly River in September:

- Mass – I was carrying a pack that meant I measured 1.24 times my normal body mass

- Distance – 25.67mi

- Cumulative elevation gain – 4495ft

- Mortality rate for Glacier national park – 260 deaths out of 102,082,878 through 2015 = 0.0000025.

So that makes our example calculation: (1.24mass x (25.67mi + 4495ft/1000) x 0.0000025 x 2 x 1000) = 0.186 total Powells and our HARM = 0.186 Powells / 25.67mi = 0.00726 Powells/mi. Note: HARM is also expressible in badassitude/mi.

Let’s compare that to the original: 1.0mass (in a boat, no carrying) x (1000mi + 0 gain in a boat) x 0.3 x 2 x 1000mi) = 800k Powells / 1000mi and thus John Wesley Powell’s HARM = 600 Powells/mi.

Bingo.

Here, try this at home. Check your own hike’s HARM and Total Powells in the handy-dandy little calculator below:

Payoff – AWE

Now, we get to the fuzzier, but more challenging (and therefore enjoyable) part of metric-building. Sure, knowing you’ve conquered a 0.2 Powell trip is invigorating, but doing it to see, say, the same view or wildlife you would have gotten within a ½mi dayhike while car-camping makes it somewhat less worth the bother. That’s where Available Wilderness Experience comes in. The AWE factor. We’ll measure AWE in Goodall’s, where 1000 Goodalls = 100% chance of the perfect wilderness experience. Beauty and magic so amazing that you come back and write My Life with the Chimpanzees (also, you love it so much you stay there for years). If you can think of more than one place you’ve been that you’d give this rating to, you’re wrong. You can’t. There can be only one perfection.

A very high AWE hike.

This will be a highly personalized measure, by necessity. Some people are wowed by seeing a double rainbow, others by mountain vistas, others by a tree they’ve never imagined could get so big. Some humble themselves in the sight of a banana slug. So what we are going to have to capture is not any kind of absolute measure, but the average expected delight gained by each hiker on the trip. Which is a fancy way to say “self-reported ratings” are about the only way we can really judge how awesome a hike is (in its literal sense). Thus, for now, we’re going to use a working definition of AWE = trail metarating out of 5 / 5 X 1000. Will we likely add modifiers such as % of spirit journeys, rainbows seen, waterfalls, and wildlife sightings? Sure, if we can get that information. But not until then. We’re multiplying by 1000 to keep it consistent with HARM.

Great. So now all we have to do is go and look up the hiker’s version of Untappd or Rotten Tomatoes or Yelp, right? Easy-peasy.

What??? No such convenient pre-existing national database exists? Huh? Internet, how can you have let me down so? Wait, what about AllTrails.com? Isn’t this exactly what they try to do? Well….yes. They try. But for our purposes, a sample size of 2 reviews on the Belly River Trail isn’t quite going to cut it. We don’t have a set maximum p value here, but that’s way way way above it. Too obscure a trail? Well, to take a non-random extremely heavily traveled trail, the Upper Yosemite Falls Trail, has all of 179 reviews.5 AllTrails is a fantastic idea, but we’ll have to give it a lot more time before we consider using it as a dataset.

So, given the lack of pre-existing datasets, we’re left with two obvious courses of action:

- Make stuff up and go for maximum comedy.

- Crowdsource a dataset and work on building it up and training the model over time

Guess which one I think is more fun?

What’s Next – The AWE project

Submit your trail ratings below! You can also access the submission form directly. Let your voice be heard in our datasets! PLEASE share with your friends, relatives, and enemies! The more people we get to start rating hikes, the better!

Potential follow-on projects:

- Collect and create a HARM database of the most (and not-most) badass hikes in North America. And then go out and do them all.

- Start comparing states by HARM and (once data becomes available) by AWE.

- Are certain types of hikes (by feature or by HARM rating) likely to be more highly rated by AWE?

Got any other ideas coming to mind? Pitch your own in the comments below, brainstorm or discuss a notion in the café, or submit a full-fledged proposal.

1 I am not worthy!^

2 As an encore, I imagine that he walked to the moon with no spacesuit using only a Wooley Mammoth for warmth. Or something along those lines.^

3 All trail measurements for my hikes were made with Locus Map Free, a handy little app that lets you download maps (in my case, USGS topographical maps) and then can use your GPS to record tracks on top of them in a non-mobile-data (or signal) environment like the middle-of-frickin’-nowhere, Montana. The page image is a screencap from Locus’ track of my Belly River Trail hike to Glenns Lake Head.^

4 People getting gored trying to take selfies with Bison in Yellowstone is actually a problem..^

5 For comparison, the number of ratings on analogous beer and movie rating platforms run 3 orders of magnitude higher. New Belgium’s Fat Tire Ale has 356,582 unique ratings on Untappd as of October 19th, 2016, The Martian has 500,872 on IMDB as of the same date. Even the book version of The Martian pulls in 435,649.^

What’s the metric unit for Powells?

Powells is the unit, it’s a measure of badassitude @rsharp. And outdoor risk.