By: James Stout

What we do when we think nobody is looking is often the best expression of who we really are. Apparently for sports fans, this means suggesting that a man with Psalms tattooed on his arm who chooses to kneel during a song = Muslim. Because he’s brown.

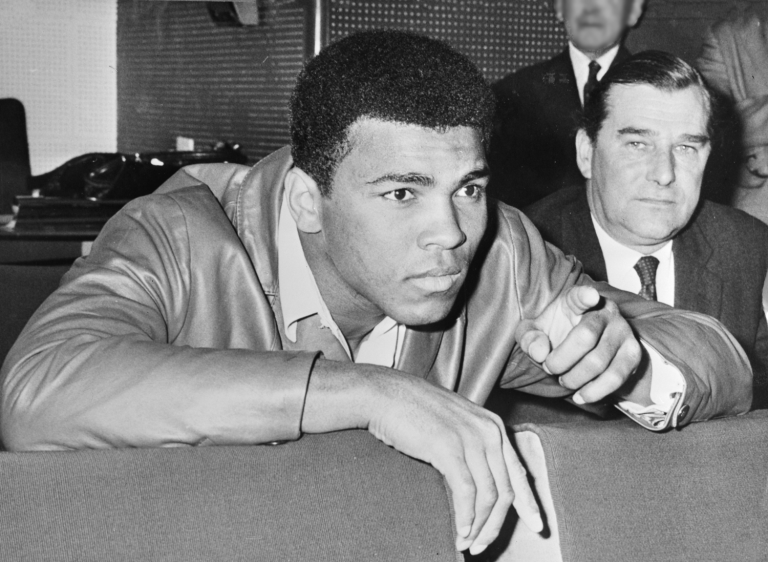

In June 2016, the world mourned Muhammad Ali, not only had we lost a great boxer but a great advocate for his community. Just months later another talented black athlete by the name of Colin Kaepernick knelt down for the national anthem and the Internet reacted in a way with which Ali would have been rather familiar. Despite all the post racial self-congratulation the US engaged in when it elected a black president, there’s much evidence to show that young black men like Kaepernick are expected by white Americans to stay in their lane, and their lane is entertainment, not emancipation.

We also know that one thing that brings the US together, and pulls it towards that middle, is sport. There is nothing more American than consuming large amounts of mediocre beer and watching grown men dressed as power rangers give each other concussions. Through the lens of sport, we can learn a lot about how we see the world. Sport is, and always has been, “serious fun” but now that fun is discussed in a searchable and recorded domain we can analyse who is having the fun, and for whom the consequences are more serious.

Sport is, as Orwell said, “war without the shooting” it gives us a chance to create and enact tribal loyalties that we can’t exhibit in our everyday lives. The importance we give to sport is not because of the games themselves, but because they let us do things that we wouldn’t do otherwise. As it turns out, sport isn’t just about the players doing things; it’s also about the fans saying things. Sport is too important not to reflect (and reflect upon) social and political issues, but it seems not to be important enough for us to use some of our more refined language. The discussions we share with our fellow fans in bleachers, bars, and even bathrooms have migrated into the public square of the 21st century; the Internet. We all know that arguments on the Internet have a unique tendency to become very offensive very fast, kind of like arguments after one Bud Light too many at the local sports bar. Unlike our hypothetical bar, however, studying conversations on the Internet does not require a warrant and a large amount of febreze.

The question

When a black athlete (like Colin Kaepernick) takes a political stance (like kneeling during the national anthem) how does this influence the use of racial epithets to describe him online?

The short-short version

It won’t surprise you to learn that taking a stance on issues facing the black community has not ended well for young Colin. In terms of discourse, we see a massive spike in terms of the use of the adjective “nigger” to modify the noun Kaepernick around the time that Kaepernick’s protest began. He’s also unemployed now despite being a hugely talented quarterback.

What might surprise you is that there was a greater number of uses of the word “Muslim” to modify Kaepernick’s name. This tells us a lot more about the Internet (and the people who use it) than it does about sport. Apparently if you mess with white America, you go in the so called Islamic State box. Oh and just to be clear, Kaepernick has bible verses tattooed on him.

The controversy

To begin with, we’ll take a look at a case you’re probably familiar with to illustrate how we’ll be using both computational linguistics tools to analyse how key sporting moments shaped the way we think about each other and the world at large. Colin Kaepernick, the black former quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers. Kaepernick began as a second stringer but took Alex Smith’s position after Smith suffered a concussion, from there he didn’t look back and led the 49ers to the 2012 Super Bowl where he scored a touchdown and passed for another. If you’re not familiar with football, I won’t bore you with the details but suffice it to say that he was very good at his job.

If you’re not familiar with football, you’ve still probably heard Kaepernick’s name, even if you only get your news through the NPR- tuned radio in your Prius. The reason you’ve heard his name is that, in 2016, he began sitting down or kneeling when the Star Spangled Banner was played before games. Why? I’ll let him tell you “[because] I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder”. Oh and just in case that wasn’t enough he had the temerity to follow a Vegan diet and once wore a t – shirt with Castro on it! So there you have it, a black athlete trying to do what white people on the Internet tell black people in sport to do: be a role model, set a positive example, make a difference in the community etc. So, now lets see how they reacted.

Methodology

Google Trends lets us explore every query in Google’s database. For the purposes of our study, Google Trends is as close as we can get to being able to eavesdrop on that Sports Bar conversation. Google Ngrams, is another massive database that searches of all the texts in the Google Books corpus printed between 1500 and 2008. This isn’t the sports bar, it’s the refined and publicly acceptable language of literature. N Grams can give us an excellent idea of how terms have become more (or less) acceptable as “fit to print”; Trends can give us an excellent idea of what might not have been so universally acceptable, but was still being said, anyways.

To get a gauge on general comments about Kaepernick in terms of race, we searched for incidences of the noun “Kaepernick” modified by the adjective “black”. To see when his race was mobilized in a purely pejorative fashion we searched for his name modified by the word “nigger” and to just see how genuinely weird the Internet is we searched for incidences modified by the word “Muslim”. Then, just to dangle the prospect of hope for a minute longer, I ran queries for the modifiers “support”, “brave” and “strong”

Results

As you can see in the visualization below, the moment Kaepernick began discussing issues related to race and social justice, incidences of racial slurs involving his name increased. Bizarrely they were outnumbered by incidences of his name modified by the adjective “Muslim” (It is worth noting at this point that Kaepernick is very open about his Christian faith and has a psalm TATTOOED ON HIS ARM). Whilst I am not sure I can entirely float in the logical stream of people using this language, I can guess that it goes something like this “Colin Kaepernick doesn’t stand for the national anthem, therefore he hates freedom. You know who else hates freedom? Daesh. Daesh are Muslim. Therefore Colin Kaepernick is Muslim”.

There was a small bump (about 15% of the size of the Muslim one) for the modifier “support” but the modifiers “brave” and “strong” didn’t even register.

It seems that, when athletes talk about politics, it is their bodies, not their words, which get judged. Words like “traitor” and “unpatriotic” register 1% of the uses of “nigger” or “Muslim”. What is important is not what Kaepernick did as much as his “otherness”.

Sport and Americanness

Colin Kaepernick is as American as they come. He was born in Wisconsin and raised by adopted white parents in Fond Du Lac. I have been to Fond Du Lac, it is about as far from Basra as you can get. He moved to Turlock, Ca as a young man and excelled at basketball and baseball more than football. He went to college at the University of Nevada on a scholarship after a coach saw him dominating a high school basketball game. He was selected by the Chicago Cubs (yes, the baseball team) in the 2009 draft but elected to pursue football instead.

What he did not do, at any point, was anything to suggest he was Muslim. A black man, raised by white parents and staunchly Christian in his religious beliefs, Kaepernick has psalms and crosses tattooed on his arms and his signature touchdown celebration involves kissing his tattoo that reads “To God the Glory”. Despite this open and clear profession of Christian faith, Kaepernick cannot seem to escape allegations that he is somehow not American. It’s hard to see past his race as the causal factor here. Our data shows similar, but smaller, spike in uses of “nigger” with his name. Given that google trends maps searches, it seems likely that people might be searching to see if he is a Muslim because they know he’s a nigger. Whatever Kaepernick says or does doesn’t seem to matter, people look at him, look at his protest and jump to the conclusion that, in a world full of racial and religious enmity, seems obvious to them.

Heck, even if we take religion out of this, the liberal Internet’s favourite supreme court justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, described the protest as “dumb and disrespectful,” saying that athletes have a right to protest “if they want to be stupid.” From where I’m reading, that looks an awful lot like she’s telling Kaepernick not to get too uppity.

This doesn’t mean sport does not have the power to make positive change. I find it hard to conceive that figures such as Muhammad Ali, Jackie Robinson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Jesse Owens have each made a change in their own way and that the way we see race has changed dramatically since (and because) Jackie Robinson first walked onto the field. But I can’t deny that Colin Kaepernick can’t seem to find a job. As for why, well if you ask Michael Bennett, the Defensive End of the Seattle Seahawks (the only team that entertained the notion of hiring Kaepernick this year), the answer is clear.

“You watch the people that really watch football, it’s middle America, and the people that buy tickets to the game aren’t really African American people… for him to bring that into that crowd was one thing that people felt like shouldn’t have been there.”

What’s next?

If this has all got a bit depressing I would like to take this final paragraph to remind you that Colin Kaepernick has a massive pet tortoise, and he sometimes lets Sammy wear his football helmet.

This method of inquiry has a lot to offer us and we would like to take it further. Muhammad Ali, Zinedine Zidane, Jackie Robinson, Pelé, Jesse Owens and many others made a real difference in how we see race, and perhaps looking at Ngrams can reveal to us how long it took for that difference to be felt. In the more contemporary era, the 2016 National Anthem protests would merit more investigation. Did white athletes who were involved receive the same hatred? We can expand this search to other countries and contexts as well. Britain went berserk for Mo Farrah in the 2012 Olympics, but how did his success influence searches using racial epithets? I really believe that sport has the power to change society, but perhaps the Internet has a more powerful way of reinforcing prejudice. Through this series, I hope to get some better answers to both of those questions.

The Greatest will now take your next question. Image credit: Dutch Nationaal Archief.

The Greatest will now take your next question. Image credit: Dutch Nationaal Archief.

No Comments on "What do sports fans search for when they think no one is looking? A Kaepernick case study"