By: Patrick W. Zimmerman

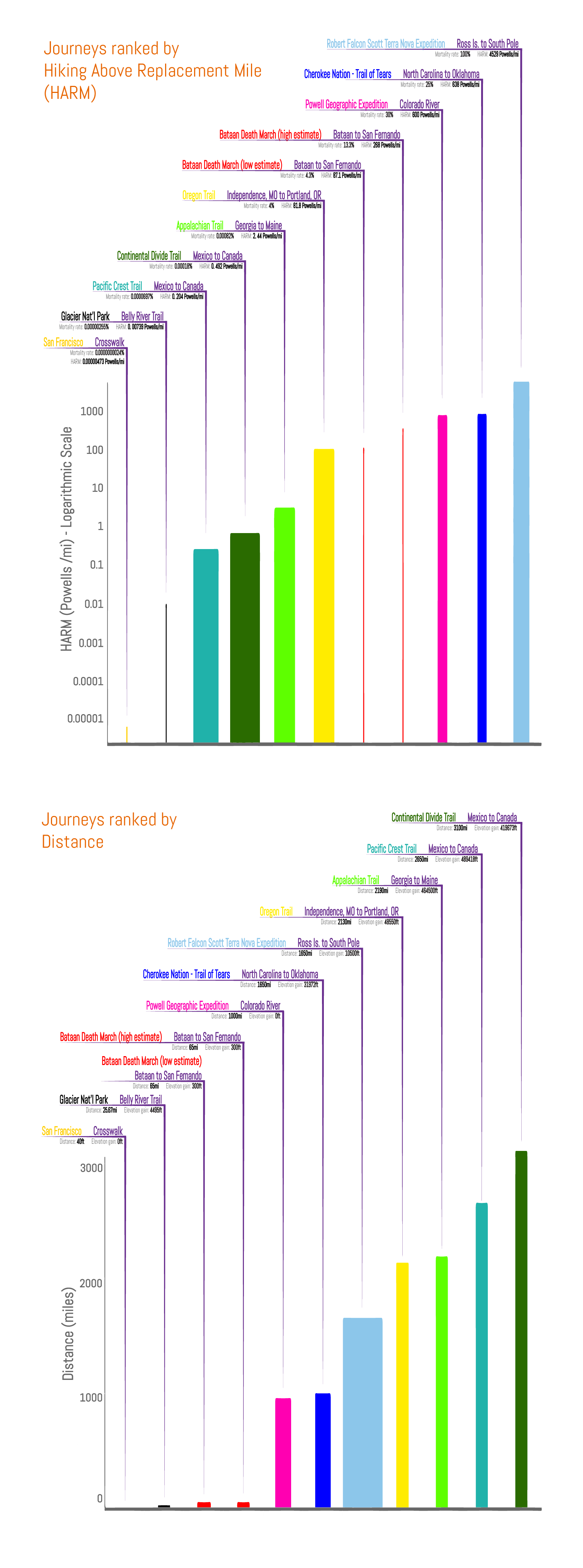

Logic dictates that the next step after proposing a new metric about trail difficulty is to make an infographic comparing a choice selection of reasonable and completely unreasonable trails. At least, that’s how logic works on the Internet. Or so I’ve been led to believe.

Thus, since we introduced Hiking Above Replacement Miles a couple weeks ago, it behooves us to take my sample short backpacking trip up among the grizzlies in Glacier National Park (the Belly River Trail to Glenns Lake Head and rank it, visually, against a set of other well-known footpaths from history.

Because if Principally Uncertain specializes in anything, it’s taking relatively rigorous, valid analytic tools and applying that analysis with a healthy embrace of the hyperbolically absurd.

Click infographic to enlarge.

Infographic notes and musings

Many of the details of trips taken in unstable, fluid, or poorly-documented environments years ago are necessarily educated guesses. They’re as accurate as I could make them with a reasonable amount of effort.

The Trail of Tears is horrifying. I had no idea before digging into this that a reasonable estimate of the mortality rate is 25%. The site hosting that info is a little dodgy (Teaching History), but the source, an Associate Professor of Colonial History at UNC Asheville, is pretty spot-on.

I got most common route and elevation estimates for National Historic Trails (Oregon Trail, Trail of Tears) by looking at the NPS Geographic Resources Division’s map and then recreating a bike map in Google Maps (walking maps in Google do not have elevation gain data). Yeah, this won’t be accurate down to the foot, but it probably is to the 1000ft, which given the scales involved is certainly close enough. Here’s the Oregon Trail Google Map. Here’s the Trail of Tears one.

The Bataan Death March is a particularly interesting case in that historians actually don’t know the death rate. They know how many people started (roughly) and how many finished, but some unknown number of POWs escaped along the way to blend with the civilian population. Since most of the POWs were Filipino (with some Americans and other), they would be effectively indistinguishable from locals once they got out of uniform (and out of the marching line). Estimates vary from 2600 total deaths to 10650, which (obviously) changes the HARM a lot.

At first glance, it’s shocking just how much more dangerous the Appalachian Trail is than the other two Triple Crown long distance trails, the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail (2-3 deaths/yr vs. 8 deaths in 37 years and 1 death in 30 years). The answer is: People. The AT doesn’t exactly go through metropolises, but it is, in general, passing through much, much more populated rural areas on its trip from Georgia to Maine than the PCT does from the Mojave Desert to the Canadian Cascades or the CDT does from New Mexico to Glacier NP. It’s the difference between almost entirely rural / protected parkland and almost entirely wilderness. Thus, the murder rate, car accident rate, and frequencies of other such people-related deaths, go up enormously.

The Terra Nova Expedition’s elevation gain was estimated from this map by Amundsen. He didn’t take quite the same route, but started at sea level and got to the South Pole by going through the same mountain range, so I’m calling it close enough.

San Francisco actually has a project estimating total volume at every single crosswalk in the city per year as part of its attempt to make the streets safer. So that made the crossing the street estimate possible. I used an estimated crosswalk length of 40ft (36ft is a standard 2-lane street) as the trip length.

The number of hikers for the Appalachian Trail, Continental Divide Trail, and Pacific Crest Trail come from their respective associations’ webpages, as do official distances and elevation gain numbers. Here’s a decent collection of deaths on the AT, one blogger’s attempt do the same for the PCT, and the only record of any fatality I could find for the CDT (though the lower number of hikers means that the mortality rate is actually a fair amount higher than that on the PCT.

For the Appalachian, Continental Divide, and Pacific Crest Trails, I used myself with my standard backpacking weight as an example hiker.

To estimate the Trail of Tears average person’s weight, I got a big assist from Rich Van Heertum (@rvanheertum), who forwarded me an article in the Int’l Journal of Epidemiology with a table for conversion of height to average weight. I found a well-researched working paper by a team at Emory University to estimate average height for Native Americans in the mid-19th Century, assumed a 50/50 split of men and women, then dropped the resulting average (137.5lbs) 10lbs to account for children. The pack weight is an estimate of what would have been carried vs. what would’ve been taken in wagons or on pack animals. You can read the full methodological discussion in this café thread.

Detailed Trail Stats

Note: numbers in italics are have a significant amount of uncertainty to them.

| Trail | Mass of hiker | Mass of pack | Elevation gain (ft) | Distance (mi) | # trips | # deaths | Mortality rate | Total Powells | HARM (Powells/mi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco Crosswalk | N/A | N/A | 0 | 40ft | 10144490823 in 2015 | 24 in 2015 | 0.00000024% | 0.0000000358 | 0.00000473 |

| Glacier NP – Belly River Trail | 170lbs | 40lbs | 4495ft | 25.67mi | 102082878 visits 1904-2015 | 260 | 0.00025% | 0.190 | 0.00739 |

| Pacific Crest Trail | 170 | 40 | 489418ft | 2650mi | 2808 in 2015 | 0.196/yr | 0.0070% | 540 | 0.204 |

| Continental Divide Trail | 170 | 40 | 419673ft | 3100mi | 150/yr | 0.026/yr | 0.0175% | 1526 | 0.492 |

| Appalachian Trail | 170 | 40 | 464500ft | 2190mi | 3064 in 2016 | 2-3/yr | 0.0816% | 5351 | 2.44 |

| Oregon Trail | N/A (assume walking alongside wagon) | N/A | 48550ft | 2130mi | 80000 | 3200 | 4% | 174284 | 81.8 |

| Bataan Death March (low estimate) | N/A | N/A | 300ft | 60mi | 60000 | 2600 | 4.33% | 5226 | 87.1 |

| Bataan Death March (high estimate) | N/A | N/A | 300ft | 60mi | 80000 | 10650 | 13.3% | 16055 | 268 |

| Powell Geographic Expedition | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1000mi | 10 | 3 | 30% | 600000 | 600 |

| Trail of Tears | 127.5lbs | 30lbs | 31972ft | 951mi | 16000 | 4000 | 25% | 607130 | 638 |

| Terra Nova Expedition | 160lbs | 200lb sleds initially | 10500ft | 1650mi | 4 | 4 | 100% | 7472250 | 4529 |

There’s something interesting about the crosswalk and Belly river examples, @pzed. Both are examples of essentially harmless activities where, over time, some mortality is encountered. This probably applies more to the longer trail than the crosswalk (with its obvious leading cause of death), but there must be some nonzero background level of HARM: for every million people who walk 20 miles in controlled surroundings, some number are going to contribute to the metric due to heart attacks, etc. and not the trail itself. On the other hand, looks like that number is pretty close to 0. So, is the Belly river value significantly larger than the background? How much of a bear bump do they get out there?

@rsharp, it’s non-zero, due to falls, bear attacks, and traffic accidents. There have been 10 fatal bear attacks in or just outside of Glacier out of a total of 260 fatalities of all types since 1904 in 101M visits. That’s a really low background level, but I would say it’s not zero when compared to the average for a 30-park sample the NPS did from 1993-1998 (443 fatalities in 446M visitors). It’s about 2.6 times as high.

Forgot to drop the link to the NPS study: here it is.